Strategies and tactics

Tackling Parkinson's more successfully requires new strategies and tactics. And we must also evaluate whether the strategies and tactics are feasible before committing to or rejecting them. Let's consider a goal that is obviously worth pursuit - improving the quality of care.

Goal: improving quality of care

At last month's International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society conference, a common theme was the need to improve the quality of care for those with Parkinson's by providing greater access to multi-disciplinary care.

Based on the model proposed by Bloem, Okun and Klein, for most people with Parkinson's the multidisciplinary care would include: physical therapist, occupational therapist, speech/language therapist, dietitian/nutritionist, psychologist/psychiatrist and social worker. In addition, there should be access for expertise such as a sleep specialist, neurosurgeon, urologist and palliative care team, in parallel with instruction for an exercise program.

Multi-disciplinary care is successful for several other diseases. But these may be different from Parkinson's - largely because of a shortage of Parkinson's centers and specialists.

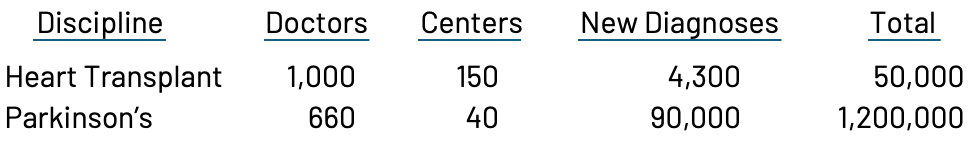

In the US, there are 40 centers of excellence in Parkinson's care, as designated by the Parkinson's Foundation with ~660 movement disorder specialists to care for people with Parkinson's. In the US, 90,000 people are diagnosed annually for a total of 1.2 million with PD.

Let's compare that to care for heart transplants (see Table below). In the US there are 150 heart transplant centers and ~1,000 physicians board certified in transplant. About 4,300 people are listed for transplant annually with ~50,000 people under the care of these heart transplant teams.

The number of patients for each doctor is alarmingly higher for Parkinson's than for heart transplant, and cardiologists often feel overwhelmed. We need a huge increase in the number of doctors treating Parkinson's.

Tactics: what resources are realistic to expect

I am a big supporter of these integrated models of care. But I've learned that pursuing a goal requires a realistic plan. Without enough movement disorders specialists or Parkinson's centers to accommodate all those people with Parkinson's, how can we reasonable expect to institute multi-disciplinary care for Parkinson's?

Option 1: increase number of physicians

To match the number of physicians to meet the needs requires a major increase in the number of doctors offered such training. Organizations such as the Parkinson's Foundation provide funding for training of physicians, but this is not enough. The Federal funding (Medicare) that supports physician training is a zero-sum game, with a fixed number of positions allocated for each hospital / medical school. These positions are then divided between all specialties - from medicine to surgery and pediatrics to psychiatry, including generalists and specialists. The competition for positions between medical specialties is fierce.

To increase the number of movement disorder specialists predictably, the Federal government would need to change its policies and mandate an increase in training positions specifically for Parkinson's - perhaps even at the expense of other specialties. Because such a plan would require policy changes in the Federal government, it does not appear to be a likely solution.

Option 2: increase the number of non-physician providers

Another approach is to increase the number of health care professionals other than physicians trained in movement disorders. Although commonly referred to as "physician extenders" - including nurse practitioners, physician assistants etc. - in many states these professionals can practice on a day-to-day basis independent of physician oversight. The roles of these providers appear to be growing slowly, and formal programs to increase the attractiveness of this professional path could be powerful tools to care for people with Parkinson's. However, this is a solution that will take years to implement and perhaps decades before commonplace. And it's not clear how such programs could be funded.

Option 3: increase the use of tech solutions

I'm not talking about artificial intelligence - necessarily. There are so many proven ways to use tech to manage many of the basic care functions. In the pre-AI era, these were referred to as dynamic web applications, and then simply web-apps.

The content displayed on a webpage or in an app would dynamically change based on the user input. Think about your experience at Amazon. On your landing page, it reminds you of your recent searches. When you start to type in what you want, it anticipates the search and delivers a page of choices, with come options tagged as being recommended. I'm not advocating for Amazon nor endorsing how well it selects recommendations for me. But imagine this dynamic advising a person with Parkinson's whether to increase their dose of a current drug or offer a phone call with a nurse. In many cases, this could prove effective even without spending the day going to and from the doctor, only to end up with the same decision about how to manage worsening symptoms from the disease. Supplementing in-person doctor appointments with phone calls is an accepted approach and Medicare even allows a doctor to bill a patient for such an activity (to be paid by Medicare; not the patient). This system exists - at least the payment mechanism to providers.

If we search for a perfect tech solution, we'll be in the development stage forever. If we look for a tech solution that could eventually address half of the questions from people with the disease, then we would have doubled the clinical capacity of the system. This would be a big step towards freeing up existing resources to create integrated care models.

Summary

I'm a big fan of integrated care models. And I'm a big fan of finding ways to make progress that are feasible and not limited by huge barriers. Tech tools can help manage Parkinson's in ways that relieve the providers of some of the daily burdens, allowing them to spend more time and energy on the tougher problems and on identifying new ways to treat the disease. With increased efficiency, resources can be used to build these multi-disciplinary care teams which would improve quality of life in so many ways for people with PD.

So those of you with tech skills and/or relationships to those with the skills: get busy. Improved quality of life is within reach.

Share This

|

Sign up at: ParkinsonsDisease.blog |

About Jonathan Sackner-Bernstein, MD

Dr. Sackner-Bernstein shares his pursuit of conquering Parkinson's, using expertise developed as Columbia University faculty, FDA senior official, DARPA insider and witness to the toll of PD.

Dr. S-B’s Linkedin page

RightBrainBio, Inc. was incorporated in 2022 to develope dopamine reduction therapy for people with Parkinson's.